Shared Vision:

The Missouri Baptist University School of Education (the “unit” here-and-after) and its administration, faculty, candidates, and community partners have a shared vision of providing educational opportunities for individuals who live and work in the St. Louis Metropolitan area and beyond. Missouri Baptist is a faith-based liberal arts university that serves a culturally diverse urban population as well as surrounding suburban and rural communities. The Unit also reaches out to a broader constituency through distance education programs serving those individuals who do not have the advantage of a local college or university. The wide diversity of the area (urban-suburban-rural) is taken into account when decisions are being made about programs, policies, and delivery systems of the unit. This concern to serve the entire community is rooted in the mission of the University which states that “(T)he University is committed to enriching students’ lives spiritually, intellectually, and professionally, and to preparing students to serve in a globally and culturally diverse society.” To this end, the unit provides programs that emphasize the importance of collaboration with partners, varied and diverse educational experiences, and critical problem-solving skills. The unit offers a context that encourages a posture that is child-centered, experientially and authentically based, culturally aware, and consistent with a Christian perspective.

In its initial and advanced programs, the unit prepares candidates to serve as competent teachers at elementary and secondary levels and also prepares candidates in advanced programs for a variety of professional and leadership roles in counseling, educational administration, and curriculum development. In keeping with the core purpose of the University, the unit is committed to “teach, empower, and inspire students for service and lifelong learning.” Candidates develop reflective and problem-solving skills through action research and experiential learning that allow them to continue to evolve as lifelong learners. Both full-time and part-time faculty are appropriately credentialed academically and are serving or have served as experienced professionals in the field. This combined background provides a climate for developing candidates who are reflective practitioners in the classroom and/or other professional contexts. Outreach efforts in the regional learning centers provide a dynamic and interactive connection with urban, suburban, and rural communities that allows the unit to continuously monitor and respond to educational needs in the larger region. The many partnerships and relationships with community colleges and PK-12 administrators, counselors, and teachers provide a rich source of feedback for continuous improvement of the unit’s programs.

In formal coursework and through diverse experiences in the field, candidates in the various initial and advanced programs are expected to develop professional dispositions that reflect the characteristics of effective and successful PK-12 teachers and other school personnel. The development of these dispositions confirms the level of learning and practice candidates have achieved in the program. The unit believes that to be successful and effective as professionals in the field, candidates should possess and demonstrate the following dispositions:

- Candidates are enthusiastic about the discipline(s) they teach/practice; appreciate the complex and ever-evolving nature of knowledge; and are committed to continuous learning about the discipline(s) they teach/practice and how individuals learn (Gardner, 2011; Sousa & Tomlinson, 2010; Tomlinson & McTighe, 2006; Woolfolk, 2010).

- Candidates appreciate multiple perspectives, convey to learners how knowledge is developed in diverse contexts, and see the connections between the disciplines they teach/practice and everyday life (Alvermann, Gillis, & Phelps, 2012; Jacobs, 2010; Tomlinson & McTighe, 2006).

- Candidates demonstrate that they understand that everyone can learn challenging concepts at high levels and persist in helping them achieve success (Gardner, 2011; Gregory, 2008; Gregory & Chapman, 2007; Costa in Ornstein, Pajak, & Ornstein, 2011).

- Candidates value flexibility and adaptability in the teaching and learning process as necessary for developing learners’ thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making skills (Bloom in Ornstein, Pajak, & Ornstein, 2011; Egbert, 2009; Wiles & Bondi, 2010).

- Candidates use learners’ strengths as a basis for growth and their errors as an opportunity for learning (Gregory, 2008; Gregory & Chapman, 2007; Marzano, 2006).

- Candidates use a variety of assessment strategies to promote growth by identifying learners’ strengths and areas in need of improvement (Alvermann et al., 2012; Gregory & Chapman, 2007; Marzano, 2006).

- Candidates are committed to reflection, assessment, and learning as an ongoing process (Caine & Caine, 2010; Marzano, Boogren, Heflebower, Kanold-McEntyre, & Pickering, 2012; Tomlinson & McTighe, 2006).

- Candidates value long- and short-term planning, but are willing to adjust those plans based on learner needs and changing circumstances (Ornstein & Hunkins, 2009; Tomlinson & McTighe, 2006; Wiles & Bondi, 2010).

- Candidates are committed to seeking out, developing, and continually refining practices that address learners’ individual needs (Caine & Caine, 2010; Gardner, 2006; Tomlinson & Imbrace, 2010).

- Candidates respect students as individuals with differing personal and family backgrounds and various skills, talents, and interests (Gardner, 2011; Haynes, 2007; Woolfolk, 2010).

- Candidates appreciate and value human diversity, show respect for students’ varied talents and perspectives, and use the multiple intelligences theory and differentiated instruction to successfully provide for diverse learning styles (Armstrong, 2009; Gardner, 2006; Gregory & Chapman, 2007).

- Candidates are thoughtful and responsive listeners who value the many ways in which people seek to communicate, and are sensitive to the cultural dimensions of communication (Alvermann et al., 2012; Bagin, Gallagher, & Moore, 2008; Egbert, 2009).

- Candidates take responsibility for establishing a safe, positive, participatory, collaborative learning environment for all students (Marzano, 2003; Marzano, Foseid, Foseid, Gaddy, & Marzano, 2005; Tomlinson & Imbrace, 2010).

- Candidates are concerned about learners’ cognitive, emotional, social, cultural, and physical well being; are alert to signs of difficulties; and are willing to consult others in the school, the home, and the community about their education and well-being (Bagin et al., 2008; Woolfolk, 2010).

- Candidates respect learners’ privacy and the confidentiality of information (Cormier, Nurius, & Osborn, 2013; Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2013).

- Candidates appreciate the role of technology in improving learning and professional productivity (Egbert, 2009; March, 2008; Prensky, 2012).

These professional dispositions reflect the vision of the unit. It is expected that candidates who demonstrate these dispositions will create an optimal learning environment and provide equitable opportunities for students to succeed and achieve their academic and career goals.

Mission of the Unit:

The mission of the unit is aligned with the mission of the University and “seeks to develop reflective, problem-solving, professional educators of excellence from a Christian perspective; to enhance the lives of students in the classroom intellectually, spiritually, physically, and socially; and to significantly influence students through the demonstrated integration of Christian faith and learning in the classroom, so that they may become positive change agents in a globally and culturally diverse society.” This means more than simply valuing human diversity; it includes an imperative to promote equity and social justice and to intentionally prepare candidates to develop the knowledge bases, interpersonal skills and dispositions for serving diverse populations. Preparing candidates to become agents of social change is consistent with the Christian perspective and is reflected not only in the classroom, but also in field experiences in diverse settings. Based on its mission, the unit has undertaken the task of ensuring each candidate has experiences in schools with students from varied socioeconomic backgrounds, varied racial and ethnic groups, English language learners, and exceptional learners.

The Model for the Conceptual Framework:

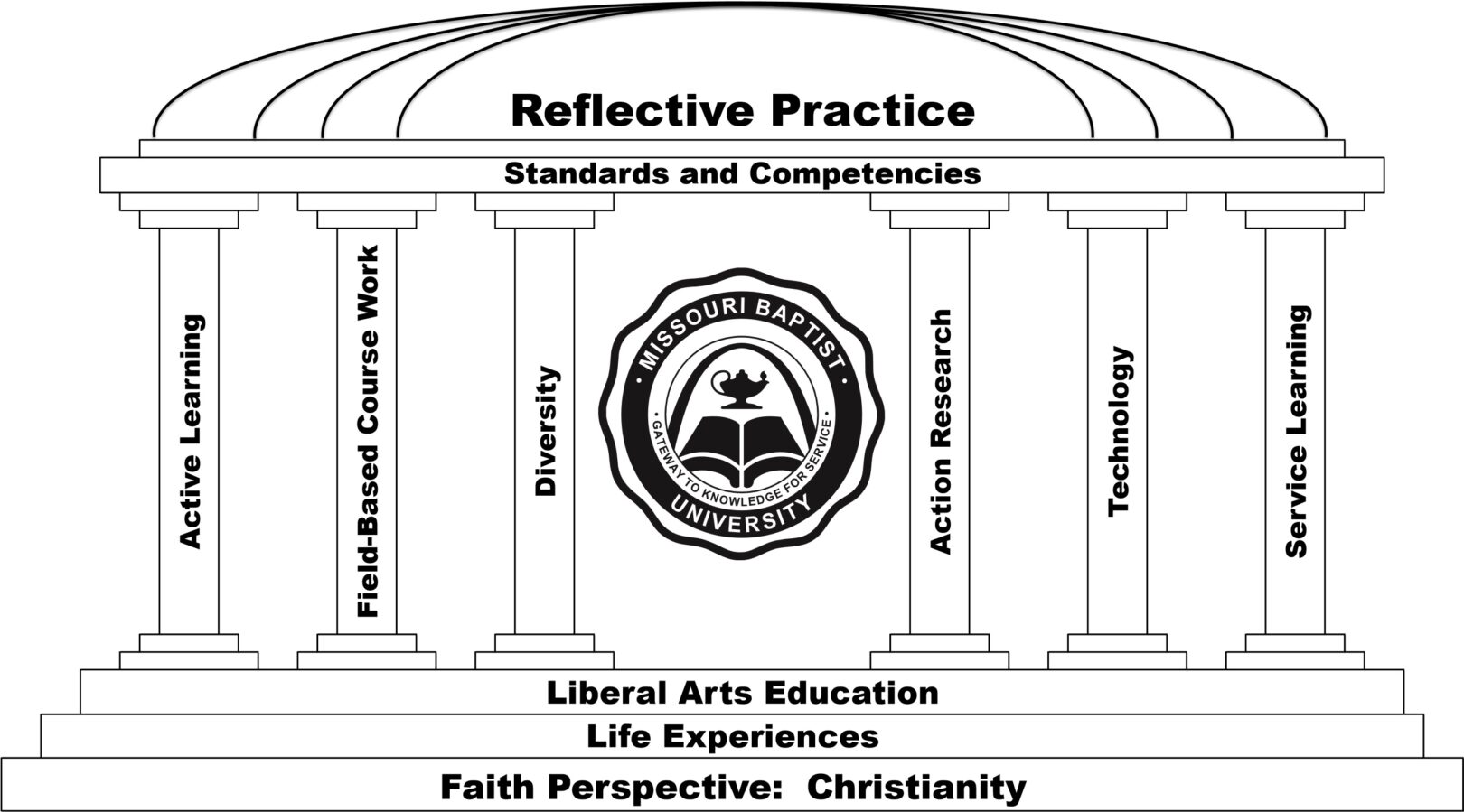

A visual model has been developed to illustrate the philosophy and knowledge bases of the unit. This model provides a representation of the unit’s commitment to enriching all students’ lives spiritually, intellectually, and professionally using a faith perspective as its foundation and integrating that perspective with the works of various educational theorists, research in the field, and the best practices of the profession. The visual model is of a building with foundational steps, six pillars, an entablature, and a dome, which together represent the various components of the educational program.

Foundational Steps

1. Faith Perspective

Just as buildings need a strong and secure foundation, the unit is built upon a foundation that integrates a faith perspective and contemporary educational theories and practices. The Christian perspective is the lens through which faculty and candidates view the teaching and learning process. This perspective is modeled on the work of Hungarian scientist and philosopher Michael Polanyi (1891-1976), whose major philosophical work stressed the Augustinian concept of fides quaerens intellectum, faith seeking understanding. Human understanding rests on a tacit belief in the reality of an objective world explored within the context of an affirming community. The faith perspective does not close down inquiry, but opens up reality so there is expectation and wonder about order and process. Polanyi believed that “into every act of knowing there enters a passionate contribution of the person knowing what is being known” (Polanyi, 1974, xiv). The rationality of the cosmos is a premise that is understood and accepted by faith. This focus on the foundation of faith, rather than closing down thinking, encourages openness to inquiry in all areas of disciplinary focus with a confidence that education and life will make sense through the process of learning.

This faith perspective on the rationality of the universe has been the framework for the establishment of many faith-based institutions. These institutions have a long and distinguished history in American education with the establishment of some of the most exemplary and prestigious universities in the country including Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Notre Dame, and Duke among others. Although some of these institutions have subsequently severed their ecclesiastical ties, hundreds of faith-based institutions of higher education continue to provide academic communities with particular missions that emphasize the importance of a breadth of knowledge in the liberal arts and specializations at the undergraduate and graduate levels to prepare individuals for various callings and careers within society.

A foundation of faith extends beyond simply believing in a rational universe, it also focuses on an ethical life that emphasizes social justice and peace (Wolterstorff, 1994). How does an individual live faithfully in relationship to a diverse social order? Education is not only the development of a specific knowledge base, but also includes forming individuals who demonstrate the importance of justice and peace in their everyday relationships in society. This requires more than just platitudes, but includes the ability to “listen” to the voices of those who are often not heard and to “embrace” those who have been marginalized and disenfranchised. As Yale theologian Miroslav Volf has argued, social justice requires “the will to give ourselves to others and ‘welcome’ them, to readjust our identities to make space for them is prior to any judgment about others, except that of identifying them in their humanity” (1996, p. 29). This commitment is indiscriminate and precedes any kind of moral evaluation of the world. Education must prepare candidates to engage the world in a way that creates social change and social justice (Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 2007). The unit is committed to preparing candidates with the knowledge and skills that assist them to interact with students from diverse backgrounds and varied viewpoints in a process that will help them to achieve their academic and career goals.

2. Life Experiences

The unit believes that candidates bring with them a lifetime of experiences to the learning process and that their socio-cultural background, spiritual beliefs, and prior academic experiences influence the development of their knowledge and beliefs about teaching and learning (Page, 2008; Payne, 2005; Posner & Vivian, 2009; Vygotsky, 1978). Pre-service teachers, administrators, and counseling candidates bring to the classroom “a strongly constructed practical theory,” based upon at least twelve years of observations and experience with traditional teaching practices (Davis, 2000). These personal theories are often firmly established and resistant to change (Rand, 1999; Rodgers & Chaile, 1998; Rodgers & Dunn, 2000; Stuart & Thurlow, 2000). The role of educator preparation, therefore, is to help candidates explore and expand upon their life-experiences and personal theories through course work and authentic field experiences (Roders & Chaile, 1998). Faculty assist candidates in broadening their perceptions of their roles as reflective, problem-solving professional educators by reflecting on their life experiences with involvement in participatory learning, classroom discussions, exploration of various theories, and experimentation with a wide variety of strategies and techniques in diverse settings with diverse populations. Furthermore, the faculty through their own teaching practices model these multiple strategies by utilizing active and participatory learning techniques, including the use of technology, reflective thinking, and exposure to contemporary literature to help candidates construct a strong foundation of professional competencies. In addition, candidates are expected to participate in professional education organizations to broaden their understanding of the profession and its standards. Organizations such as Kappa Delta Pi, Student Association of Curriculum and Supervision Development, and Student Missouri State Teachers Association provide candidates opportunities for leadership and the advantage of networking with future teachers, counselors, and administrators. This professional growth experience instills awareness that education is a profession requiring continual personal, pedagogical, and practical development.

3. Liberal Arts Foundations

Traditionally, even the most conservative faith-based institutions have emphasized the importance of a breadth of knowledge that supports and provides a foundation for areas of specialization. Depth of knowledge in the liberal arts contributes to the formation of a whole person who recognizes that specific knowledge and skills are necessary to provide an integrated context for developing special skills (Ryken et al., 2012). The general education program at Missouri Baptist University places a strong emphasis on a broad, cohesive foundation in the arts, languages, the natural, social, and behavioral sciences, literature, and the humanities. These broad disciplinary studies are also bolstered by courses on critical thinking and writing. The general education program helps candidates gain a wider and more diverse vision of the world that undergirds the specialized knowledge base, methods, and practices in the field of education. The faculty and administration of the University believe without this foundation, candidates may become proficient to perform particular tasks, but will be limited in their understanding of the world.

It is assumed that candidates in advanced and graduate programs enter these programs with a strong general education background. Advanced programs build on an undergraduate degree that provides evidence of a strong general educational foundation regardless of where the degree is completed. Candidates are expected to demonstrate, for example, strong writing skills and to engage in critical thinking in all advanced classes. These expectations are reflected in the course and program objectives in all advanced programs. Although the state Articulation and Transfer policies attempt to guarantee an equivalency in general education background, candidates may be required to receive remedial assistance if they are considered to be deficient particularly in writing, technology, and critical thinking. The unit believes that administrators, teacher leaders, curriculum specialists, and counselors are expected to have a broad understanding of the various disciplines, such as science, math, social studies, and literature, to help teachers and students improve within the P-12 system. A breadth of knowledge is necessary for professionals to examine and assess significant cultural, social, and economic changes in the environment that may seriously influence the future of P-12 programs and every student’s ability to access quality educational programs.

Pillars

Bruner describes the educator’s role as performing the job of “scaffolding” the learning task so it is possible for students to internalize knowledge (Wertsch, 1985). The Unit provides “pillars of support” (scaffolds) designed to create competent teachers, counselors, and educational administrators (Moss & Brookhart, 2012). These pillars are essential for the development of professional practitioners, and through a scaffolded approach, the responsibility for learning is shared by faculty and candidates. The architectural model of the building identifies the following supports:

1. Theoretical Orientation: Active Learning

Candidates begin their academic experience with a variety of social, religious, and economic backgrounds. They have different perspectives about life that may or may not be helpful in the process of learning. The responsibility of the Unit faculty is to challenge the candidates’ prior knowledge by engaging them in active learning and participatory study to stimulate critical and reflective thinking. The purpose of active learning is not to negate previous beliefs and knowledge, but to encourage candidates to construct a belief system based on the relationship between prior knowledge and new knowledge acquired while interacting with faculty, candidates, and professionals in the field so they will integrate these personal experiences and critical reflection (Bonwell & Eison, 1991).

The unit faculty do not believe that learning is a passive transmission of information, but assumes that learners actively create new knowledge based on a foundation of previous learning (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Hoover, 1996). This new knowledge is organized in networks that are increasingly more complex and abstract. This constructed knowledge is under a nearly continuous state of reorganization and restructuring (Noddings, 2007). Learning is not simply the retrieval of rote-learned facts where knowledge is poured into the minds of learners by giving them information. Knowledge is constantly evolving and changing as learners have new experiences that cause them to build on and modify their prior knowledge (Reeves, 2011; Sidani-Tabbaa & Davis, 1991). Candidates are active participants in the learning process whether they are experiencing new concepts in factual knowledge, pedagogical and professional knowledge, or new roles. Action combined with critical thinking and reflection helps individuals construct new understandings (Ammon & Levin, 1993; Mansilla & Gardner, 2008).

The belief in active learning and critical thinking does not suggest that teacher candidates have no active role in knowledge construction, since “any interpretation is as good as any other” (Borko, Davinroy, Bliem, & Cumbo, 2000, p. 275). Rather, teachers and other school professionals serve as guides, facilitators, coaches, and co-explorers who encourage learners to “question, challenge and formulate their own ideas, opinions, and conclusions” (Abdal-Haqq, 1998, p.1). Educators must be aware of candidates’ incomplete understandings or conflicting beliefs and strive to build upon their ideas to help them reach a more mature understanding of these concepts (Bransford et al., 2000). In ongoing research and policy statements, such as “Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs” by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (2009), “Principles and Standards for School Mathematics”by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2000), “Breaking Ranks: Changing our American Institutions” by the National Association of Secondary School Principals (1996), and “Studying Teacher Education: The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education by the American Educational Research Association’s Panel on Research and Teacher Education (2005), educators have called for a change from the traditional teaching practices of the past to strategies that encourage candidates’ critical thinking skills through active learning.

2. Field-Based Coursework: Scaffolded Field Experiences

The unit’s educator preparation programs at both the initial and advanced level are based upon the belief that learning is developmental and is built on prior knowledge and experiences (National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education, 2010). Field experiences for all educator programs are carefully sequenced to provide support for candidates as they gain professional and pedagogical knowledge and skills (Bransford, Derry, Berliner, & Hammerness, 2005). Support for learning at every level requires giving information, prompts, reminders, and encouragement at the right time in the right amount, and then gradually allowing the candidate to do more and more independently (Moss & Brookhart, 2012). Faculty assist learning by adapting materials and problems to candidates’ current developmental levels, demonstrating skills or thought processes, introducing candidates to complex educational issues, and giving feedback or asking questions that refocus the candidates’ attention until they mature into independent professionals in their own respective fields of endeavor (Koenig, 2010; National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education, 2010). In addition to the carefully sequenced field experiences, the unit requires initial teacher preparation candidates to participate in an urban experience which provides them with a concentrated experience where they work with faculty and students from a variety of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. The unit also develops P-12 partnerships throughout eastern Missouri with school districts so that candidates may participate in even more extended experiences in contexts that will enhance their ability to work more effectively with diverse populations.

The phase-specific, scaffolded experiences are similar across programs including teacher education, school counseling, administration, library media, special reading, and psychological examiner programs. Each program follows this developmental process:

- Phase I: Exploring the Profession — This phase is an introduction to the field with observations and shadowing experiences in classroom, counseling and administrative settings. The purpose of this phase is to allow candidates the opportunity to experience particular settings and various student behaviors in age-appropriate groups (Posner & Vivian, 2009). These experiences also allow candidates to reflect on their career choice and to observe and evaluate the developmental needs of students to determine whether it is the age group they feel is the best fit.

- Phase II: Immersion in the Profession – During this phase candidates increasingly become participants in educational settings with P-12 students in their chosen level of development. Candidates are required to participate in the professional process in diverse settings whether it includes teaching, counseling, or administrative activities. Candidates assume more independence in the planning and development of instructional, counseling, and administrative strategies, but continue to benefit from ample faculty and professional support. These field experiences are combined with multiple opportunities for reflective discussion, student interaction, problem-solving, and writing in a journal. An integral part of these courses and field experiences is the interchange of ideas among the candidates, field supervisors, and faculty (Cushner, McClelland, & Safford, 2011).

- Phase III: Professional Internship – Candidates spend more intensive and concentrated time in school, district, or clinical settings during this phase and are responsible for student learning, student educational and behavioral problems and concerns, and district needs. Candidates begin to immerse themselves into their chosen educational career from a professional perspective rather than a candidate’s perspective. During Phase III candidates are required to meet with faculty supervisors in a university classroom setting to discuss their internship experiences, share ideas and concerns, and collaborate with colleagues about professional roles and responsibilities. Candidates are expected to converse daily with cooperating teachers and other designated professionals involved in the field experience as an integral part of the reflective process. Experiences during this phase are conducted in different contexts and settings to ensure sustained opportunities with diverse communities.

3. Emphasis on Diversity and Social Change

As indicated earlier, a faith-based approach to education emphasizes not only the importance of helping candidates to understand and to respond to a diverse society, but also the commitment to social justice and change. The unit believes that educators who understand the value of diversity also have a moral imperative to embrace diversity and advocate for social change. Justice for every person regardless of race, gender, ethnic or national origin, age, socioeconomic status, or disability is one of the guiding principles of American democratic society and appreciation of diversity is a tool for justice and social change (Adams et al., 2007; Soler, Walsh, Craft, Rix, & Simmons, 2012).

In an effort to promote equity and social justice, the unit provides diverse experiences for candidates in field-based coursework, the practice of educational strategies (teaching, counseling, and leadership), and the development of dispositions related to diversity (Sue & Sue, 2012). The valuing of diversity is also reflected in the attitudes, perceptions, and goals of the faculty, administrators, and supervisors of the unit (Banks, 2001). The unit emphasizes the importance of candidates developing both the knowledge base and interpersonal skills and attitudes for serving diverse populations (Higgins, MacArthur, & Kelly, 2009; Stier, 2003; Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992). As part of the process for achieving this goal, the unit has established competencies related to diversity and continues to evaluate and revise syllabi in every program to ensure that these competencies are addressed and assessed.

As previously indicated, preparing candidates to become social agents requires not only course work, but also field experiences in diverse settings. Recent trends in American education illustrate the disparities in learning and achievement between high and low socioeconomic communities and the importance of developing strategies that meet the needs of these students (Jensen, 2009; Kozol, 2005). The unit requires that all candidates have experiences with students from varying socioeconomic backgrounds, students from different ethnic groups, students who are English Language Learners, and students with exceptionalities.

4. Action Research

The unit embraces the model of the teacher/researcher and incorporates action research in both the initial and advanced programs. Action research, as currently understood in the field, has been defined as “a process in which participants examine their own educational practice, systematically and carefully, using the techniques of research” (Watts, 1985, p. 119). This method has evolved into a credible process for individual teacher and school district improvement (Dimetres, 2010; Schmuck, 2006). This cyclical inquiry leads to a process where teachers, counselors, and administrators continually observe, evaluate, and revise their instruction and other strategies as they learn more about themselves and their students (Bruce & Pine, 2010; Robinson & Lai, 2006).

Teacher certification students in the unit are introduced to action research concepts in the two Folio courses (EDUC 201 Professional Growth and Folio Development I and EDUC 401 Professional Growth and Folio Development II), and are required to complete an action research study in several subsequent education courses, culminating in the Action Research Project completed during student teaching.

Advanced candidates in masters’ programs (curriculum, teaching, technology, and administration) are required to take GRED 543 Methods of Inquiry I in which a variety of research methods are explored, with an emphasis placed on action research. An action research study is completed during the masters’ programs. Candidates in both tracks of the Educational Specialist programs are also required to complete a data-focused course, GRED 663 Data-Analysis for Decision-Making. The Doctor of Education program requires two additional research courses which focus on either quantitative or qualitative methods, GRED 753 Methods of Inquiry II and GRED 763 Methods of Inquiry III. Doctoral candidates must complete a dissertation which must be approved by a dissertation committee after completion of an oral defense. Two additional courses in the doctoral program, EDUC 723 Transformational Theories and Applications, and EDAD 743 Advanced Strategic Planning, include field-based research as a component of the course.

5. Integration of Technology in Coursework and Field Experiences

One goal of the unit is to integrate technology into all coursework and field experiences for the teacher education, counseling, and administration programs (Rosaen, Shram, & Herbel-Eisenmann, 2002). Candidates at the University are introduced to technology as a degree-requirement. Candidates in undergraduate educational programs are required to complete EDUC 373 Technology and Instructional Media. The Education faculty builds on this knowledge with assignments requiring candidates to demonstrate their competency in technology in subsequent coursework and field experiences (Forcier & Descy, 2008; NETS, 2007; NETS, 2008). Candidates are also required to document their competency in the use of technology with artifacts that are included in their summative portfolio prior to graduation. The University library has implemented e-Library in science and education and University classrooms have been updated with the latest technology for instructional purposes. Technology training for faculty includes workshops and in-service activities. Most faculty are also trained to use the BlackBoard Classroom Management System for either hybrid or asynchronous online courses and programs. All online faculty are Learning Resource Network (LERN) certified and are required to take additional online training at the advanced level. Faculty utilize their training to enhance candidates’ pedagogical and professional knowledge and skills (Bai & Ertmer, 2008; Prensky, 2012; Egbert, 2009).

Candidates in the masters’ programs are required to complete EDUC 573 Application of Technology and, as with undergraduate candidates, must demonstrate competency in the use of technology in their completed portfolios. The Methods of Inquiry courses (I,II,III) also include the use of an electronic statistical program to analyze data and doctoral candidates use this package for their formal project. During the program and field experience opportunities, candidates are encouraged to enhance their instruction and PK-12 student learning with the use of technology (Chen & Thielemann, 2008).

6. Service Learning

The unit believes that students of all ages develop morally, emotionally, and socially as they become actively involved and solve real-life problems with peers, adults, and the community. This emphasis is in keeping with the view of Tyler who argues that learning occurs “through the active behavior of the student; it is what he does that he learns, not what the teacher does” (1942, p. 63). Many of the seminal theorists in the field of education and moral development stress that to provide a framework for learning, schools must integrate experiential learning into the curriculum (Kinsley & McPherson, 1995). Through active involvement and situational problem-solving, candidates become cognizant of and sensitive to the needs of others. Service learning provides a stimulus that helps candidates develop moral behavior and character, foster an ethic of service to the community, and build positive relationships with peers and adults as well as individuals in diverse contexts (Eyler & Giles, 1999). Community service experiences integrated into the curriculum provide opportunities for candidates to make real contributions to their school and community. In both the initial and advanced programs, including the doctoral program, candidates engage in field experiences and applied research in an effort not only to identify difficult issues but to seek solutions to real problems. Many of the service learning activities prepare candidates for working in diverse school settings, including urban, suburban, and rural schools, developing structure for students with unique needs that require creative and varied strategies.

Entablature: Standards and Competencies

The entablature is the “plate” that sits on top of the pillars and supports the dome. It both supports and secures the rest of the structure. With this in mind, the unit seeks to produce reflective, problem-solving professionals who demonstrate competencies adopted by the Missouri State Board of Education, the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP), and unit competencies which provide the standards for preparing teachers, counselors, and school administrators. It is imperative that the goals of the unit meet state and national standards of performance to provide quality educator preparation programs. This is why the competencies required of the unit’s candidates are aligned with state and national standards. These standards provide an external framework for assessing the level of quality for the unit’s programs to ensure that expectations are equivalent to or exceed those of institutions throughout the state and nation. A thread that runs throughout the standards, at both the state and national level, is the importance of preparing candidates to be self-directing, self-motivating, and self-modifying. The unit attempts to assist candidates to continuously move in the direction of autonomy through its phase-specific, developmental process. Because candidates are continuously experimenting and gaining new knowledge, the standards provide important markers for assessing their level of achievement in meeting this goal.

Dome: Reflective Practice

The dome in the architectural model used for the conceptual framework is the over-arching structure that pulls together all the other components including the foundation, the pillars, and the entablature. Through the process of reflective practice and assessment, the unit is able to determine whether what has been learned and achieved is integrated into a whole, indicating that the candidate is appropriately prepared for entry into the profession. The performance outcomes are measurable results that indicate what the candidate has learned in the various programs and are assessed to determine whether the program is accomplishing its mission.

A primary task of the unit is to develop candidates who are self-reflective, problem-solving professionals who are life-long learners and who demonstrate the competencies required for professionals in the field (Hammerness, Darling-Hammond, & Bransford, 2005). Reflective professionals do not take learning for granted; rather they constantly challenge themselves and their students to apply critical thought, analysis, interpretation, and synthesis to information as opposed to simply accepting information without judicious reasoning (Barnett, Copland, & Shoho, 2009; Brookfield, 1995). Educators who rely on habitual behavior, impulse, custom, or authority, will have a difficult time growing as professionals. Reflective thinking also entails the ability to self-assess, to determine where one’s level of knowledge and skills fit in terms of the standards and overall expectations of the profession (Rodgers & Scott, 2008). Reflective thinking is composed of many parts and indicates the individual desire to engage in inquiry and aggressively seek self-awareness, self-knowledge, and new insights into the world of professional practice (Brookfield, 1995). The unit strongly values reflection as an instrument for growth and expects its candidates to engage in reflective practice as an integral tool that ensures professional growth. The faculty model reflective thinking in their engagement with candidates, their ability to assess their own knowledge and skills, their interest in changes in theory and practice, and in their scholarly pursuits related to the field of education.

The curricula for teacher preparation, educational leadership, and counselor education are designed to integrate critical thinking throughout the program. It is also an integral component of instructional strategies emphasized by the unit. Candidates are expected to critically relate the knowledge and practices of their study and practice to the standards and competencies of the program through writing and participatory dialogue. Education courses are expected to provide specific opportunities for candidates to practice reflective thinking by relating the content of classroom discussions and dialogue to their personal paradigms. Critical reflection leads to the construction of new knowledge and insight from the interchange of ideas (Brookfield, 1995). Candidates are expected to continually improve their sophistication and the depth of their reflection as they progress through the program (Estes, Mintz, & Gunter, 2010). There is an expectation of developmental progression of critical thought as the candidates move through the program that corresponds to the phases of exploration, immersion, internship, and induction into the profession.

Performance Outcomes

In addition, the unit has identified a number of outcomes that relate candidate expectations to the state and national standards and to the mission of the University. Each of the outcomes for teaching and other school professions also correspond to one or more of the architectural features described in the conceptual framework. The key outcomes require that candidates display the following:

- Consistently demonstrate the content, pedagogy, and pedagogical content knowledge skills, competencies, and dispositions defined as appropriate in their area of responsibility (Estes et al., 2010; Gardner, 2011; Jacobs, 2010; Sousa & Tomlinson, 2010).

- Analyze and reflect on their practice using a variety of assessment strategies including action research and provide evidence that they are committed to professional development (Caine & Caine, 2010; Marzano, et al., 2012; Tomlinson & Imbrace, 2010).

- Observe and practice solutions to problems of practice in diverse clinical settings and with diverse PK-12 populations (Armstrong, 2009; Gardner, 2011; Haynes, 2007; Woolfolk, 2010).

- Use their self-awareness and knowledge of diversity to create learning environments that support their belief that through active hands-and-mind-on learning all students can learn challenging curriculum (Cushner et al., 2011; Posner & Vivian, 2009; Sue & Sue, 2012).

- Demonstrate and promote the strategic use of technology to enhance learning and professional practice (Egbert, 2009; March, 2008; Prensky, 2012).

- Support schools, students, and the community through leadership, service, and personal involvement (Bagin et al., 2008; Farina & Kotch, 2008).

- Develop effective and supportive relationships that enhance communication among students, parents, and colleagues to facilitate learning (Bagin et al., 2008; Caine & Caine, 2010; Egbert, 2009; Farina & Kotch, 2008).

- Exhibit empathy for and sensitivity to students and colleagues (Caine & Caine, 2010; Jacobs, 2010; Woolfolk, 2010).

- Actively practice the profession’s ethical standards (Bagin, Gallaher, & Moore, 2008; Cormier, Nurius, & Osborn, 2013; Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2013).

These performance outcomes are assessed in multiple ways throughout the program. Ultimately, they indicate whether the candidate is prepared to enter the profession with the basic knowledge and skills necessary to practice as a professional in the field. These outcomes are expected to be a starting point for a life of learning that designates a continual process of self-directed reflective thinking, collecting and analyzing data, acquiring solutions for change, and implementing strategic change based on action research (Guskey, 2008).

Assessment

Institutional objectives reflect the mission of the University as well as the Christian, liberal arts emphasis. The institutional abilities expected of all candidates at MBU are as follows:

- Critical Thinking

- Integration of Faith and Learning

- Diversity/Globalization

- Oral and Written Communication

- Social Interaction

- Aesthetic Engagement

- Use of Technology

The unit, program, and course objectives and outcomes reflect the general learning and broad core expectations of candidates majoring in a particular field or discipline, i.e. knowledge bases, attitudes, skills, and abilities. There is a correlation between the institutional objectives and the program objectives.

A systematic and multi-dimensional plan for assessment has been developed for teacher, school leader, counselor education candidates, and other school personnel. This plan employs a variety of internal and external assessment strategies to measure each candidate’s readiness to be admitted to the profession of education with the requisite knowledge, skills, and dispositions appropriate for the expected roles and responsibilities as defined by the unit, the State of Missouri, NCATE, and the program appropriate learned societies (Armstrong, 2006; Cochran-Smith & Power, 2010). The unit defines “internal assessment” as a tool or method of evaluation developed and/or implemented by the faculty and “external assessment” as a tool or method of evaluation designed and/or implemented by an organization (such as ETS) or a faculty member/professional/partner external to the unit or institution (Rowntree, 1987). Assessment is accomplished at varying levels (course, program, and unit) and throughout the three developmental phases of each program. Candidates are assessed based on unit, state and national standards including content knowledge, professional and pedagogical knowledge, and dispositions. Although each program has assessments specific to that program, both initial and advanced programs have common assessments in which data are collected and analyzed at multiple points in each program to determine candidates’ development and growth in the program (Willis, 2006). The unit has an annual cycle of collecting, analyzing, and reporting data from assessments to make necessary and timely changes in the program (Willis, 2006).

Sources:

Abdal-Haqq, I. (1998). Constructivism in teacher education: Consideration for those who would link practice to theory. (Report SP 038 284). Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teaching and Teacher Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 426 986)

Adams, M., Bell, L.A., & Griffin, P. (2007). Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.Alvermann, D. E., Gillis, V. R., & Phelps, S. F. (2012). Content area reading and literacy: Succeeding in today’s diverse classrooms (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Ammon, P., & Levin, B. B. (1993). Expertise in teaching from a developmental perspective: The developmental teacher education program at Berkeley. Learning and individual Differences, 5 (4), 319-326.

Armstrong, T. (2006). The best schools: How human development research should inform educational practice. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Armstrong, T. (2009). Multiple intelligences in the classroom (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Bagin, D., Gallagher, D. R., & Moore, E. H. (2008). The school and community relations (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Bai, H., & Ertmer, P. A. (2008). Teacher educators’ beliefs and technology uses as predictors of preservice teachers’ beliefs and technology attitudes. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 16(1), 93-112.

Banks, J. A. 2001. Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching, 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Barnett, B. G., Copland, M. A., & Shoho, A. R. (2009). The use of internships in preparing school leaders. Young, M. D., Crow, G. M., Murphy, J., & Ogawa, R. T. (Eds.). Handbook of research on the education of school leaders. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bloom, B. S. (2011). The search for methods of instruction. In A. C. Ornstein, E. F. Pajok, & S. B. Ornstien (Eds.). Contemporary issues in curriculum (pp. 229-234). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. Washington DC: ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1.

Borko, H., Davinroy, K. H., Bliem, C. L., & Cumbo, K. B. (2000). Exploring and supporting teacher change: Two third-grade teachers’ experiences in a mathematics and literacy staff development project. The Elementary School Journal, 100(4), 273-306.

Bransford, J. K., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience and school (Exp. Ed.). Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Bransford, J., Derry, S., Berliner, D., & Hammerness, K. with Beckett, K.L. (2005). Theories of learning and their roles in teaching. Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (Eds.). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 40-87). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bruce, S. M., & Pine, G. P. (2010). Action research in special education: an inquiry approach for effective teaching and learning. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Caine, G., & Caine, R. (2010). Strengthening and enriching your professional learning community: The art of learning together. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Chen, I., & Thielemann, J. (2008). Technology application competencies for K-12 teachers. Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Power, C. (2010). New directions for teacher preparation. Educational Leadership, 67(8), 6-13.

Cormier, S., Nurius, P., & Osborn, C. (2013). Interviewing and change strategies for helpers (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Costa, A. L. (2011). The thought-filled curriculum. In A. C. Ornstein, E. F. Pajok, & S. B. Ornstein (Eds.), Contemporary issues in curriculum (pp. 229-234). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Cushner, K., McClelland A. & Safford. P. (2011). Human diversity in education: An intercultural approach (7th ed). Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages

McClelland A. & Safford. P. (2011). Human diversity in education: An intercultural approach (7th ed). Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

Davis, S. C. (2000). Using children’s work to reflect on teaching: One early childhood student teacher’s reflections. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 21 (2), 185-192.

Dimetres, P. (2010). Professional learning & accountability. Retrieved from http://www.fcps.edu/plt/tresearch.htm.

Egbert, J. (2009). Supporting learning with technology: Essentials of classroom practice. Columbus, OH: Pearson.

Estes, T. H., Mintz, S. L., & Gunter, M. A. (2010). Instruction: A models approach (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Eyler, J., & Giler, D. (1999). Where is the learning in service-learning? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Farina, C., & Kotch, L. (2008). A school leader’s guide to excellence: Collaborating our way to better schools. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Forcier, R. C., & Descy, D. E. (2008). The computer as an educational tool: Productivity and problem solving (5th ed.). Old Tappan, NY: Pearson.

Gardner, H. (2006). Multiple intelligences: New horizons in theory and practice. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011). The unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should teach. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gregory, G. H. (2008). Differentiated instructional strategies in practice: Training, implementation, and supervision. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Gregory, G. H., & Chapman, C. (2007). Differentiated instructional strategies: One size doesn’t fit all.Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Guskey, T. R. (2008). The rest of the story. Educational Leadership, 65(4), 28-35.

Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J. with Grossman, P., Rust, F., & Shulman, L. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (Eds.). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Haynes, J. (2007). Getting started with English Language Learners: How educators can meet the challenge. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Higgins, N., MacArthur, J., & Kelly, B. (2009). Including disabled children at school: Is it really as simple as ‘a, c, d’?. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(5), 471-487.

Hoover, W.A. (1996). The practice implications of constructivism. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory News, p. 1.

Jacobs, H. H. (2010). Curriculum 21: Essential education for a changing world. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Jensen, E. P. (2009). Teaching with poverty in mind: What being poor does to kids’ brains and what schools can do about it. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2013). Psychological testing: Principles, applications, & issues (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Kinsley, C. W. & McPherson, K. (1995). Enriching the curriculum through service learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Koenig, R. (2010). Learning for keeps: Teaching the strategies essential for creating independent learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kozol, J. (2005). The shame of the nation: The restoration of apartheid schooling in America. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Mansilla, V. B., & Gardner, H. (2008). Disciplining the mind. Educational Leadership, 65(5), 14-19.

March, T. (2008). Intriguing ourselves to death. Retrieved from www.ozline.com/writings/intriguing-ourselves-to-death.

Marzano, R. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research-based strategies for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Marzano, R. J. (2006). Classroom assessment and grading that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Marzano, R. J., Boogren, T., Heflebower, T., Kanold-McEntyre, J., & Pickering, D. (2012). Becoming a reflective teacher. Bloomington, IN: Marzano Research Laboratory.

Marzano, R. J., Foseid, M. C., Foseid, M. P., Gaddy, B. B., & Marzano, J. S. (2005). A handbook for classroom management that works. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Moss, C. M., & Brookhart, S. M. (2012). Learning targets: Helping students aim for understanding in today’s lesson. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. Retrieved from http://www.naeyc.org.

National Association of Secondary School Principals (1996). Breaking ranks: Changing our American institutions. Retrieved from http://www.nassp.org.

The National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (2010). Transforming teacher education through clinical practice: A national strategy to prepare effective teachers. Retrieved from www.ncate.org.

The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. Retrieved from http://www.nctm.org.

Noddings, N. (2007). Philosophy of education (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Ornstein, A. C., & Hunkins, F. P. (2009). Curriculum: Foundations, principles, and issues (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Page, M. (2008). You can’t teach until everyone is listening: Six simple steps to preventing disorder, disruption, and general mayhem. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Payne, R. (2005). A framework for understanding poverty (4th ed.). Highlands, TX: aha! Process, Inc.

Polanyi, M. (1974). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Posner, G. J., & Vivian, C. T. (2009). Field experience: A guide to reflective teaching (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Prensky, M. (2012). From digital natives to digital wisdom: Hopeful essays for 21st century learning.Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Rand, M. (1999). Supporting constructivism through alternative assessment in early childhood teacher education. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 20 (2), 125-135.

Reeves, A. R. (2011). Where great teaching begins: Planning for student thinking and learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Robinson, V., & Lai, M. K. (2006). Practitioner research for educators: A guide to improving classrooms and schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Rodgers, C. R., & Scott, K. H. (2008). The development of the personal self and professional identity in learning to teach. Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S., & McIntyre, D. J. (Eds.). Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed.) (pp. 732-755). New York, NY : Routledge and ATE.

Rodgers, D. B., & Chaille, C. (1998). Being a constructivist teacher educator: An invitation for dialogue. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 19 (3), 203-211.

Rodgers, D. B., & Dunn, M. (2000). Communication, collaboration, and complexity: Personal theory building in context. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education. 21 (2), 273-280.

Rosaen, C. L., Shram, P., & Herbel-Eisenmann, B. (2002). Using technology to explore connections among mathematics, language, and literacy. Contemporary issues in technology and teacher education (online serial), 2(3). Retrieved from http://www.citejournal.org/vol3/iss3/mathematics/article1.cfm.

Rowntree, D. (1987). Assessing students: How shall we know them? East Brunswick, NJ: Nichols Publishing.

Ryken, L., Litfin, D., Jacobs, A., Lundin, R., Mead, M. L., Wood, J.,…Wilhoit, J. (2012). Liberal arts for the christian life. Davis, J. C., & Ryken, P. G. (Eds.). Wheaton, IL: Crossway.

Schmuck, R. A. (2006). Practical action research for change (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Sidani-Tabbaa, A., & Davis, N. (1991). Teacher empowerment through change: A case study of a biology teacher. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Teacher Educators, New Orleans, LA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 330 670)

Soler, J., Walsh, C. S., Craft, A., Rix, J., & Simmons, K. (2012). Transforming practice: Critical issues in equity, diversity and education. Stoke-on-Trent Staffordshire, England: Trentham Books.

Sousa, D., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2010). Differentiation and the brain: How neuroscience supports the learner-friendly classroom. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Stier, J. (2003). Internationalisation, ethnic diversity and the acquisition of intercultural competencies. Intercultural Education, 14(1), 77-92.

Stuart, C., & Thurlow, D. (2000). Making it their own: Preservice teachers’ experiences, beliefs, and classroom practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 51 (2), 113-121.

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2012). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (6th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Sue, D. W., Arredondo, P., McDavis, R. (1992). Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: Acall to the profession. Journal of MulticulturalCounseling & Development, 20 (2), 64-89.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbrace, M. B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., & McTighe, J. (2006). Integrating differenciated instruction and understanding by design: Connecting content and kids. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Tyler, R. W. (1942). Appraising and recording student progress adventure in American education(volume III). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Volf, M. (1996). Exclusion & embrace: A theological exploration of identity, otherness, and reconciliation. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Vygotsky, L. V. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watts, H. (1985). When teachers are researchers, teaching improves. Journal of Staff Development, 6(2), 118-127.

Wertsch, J. (1985). Culture, communication, and cognition: Vygotskian perspectives. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Wiles, J., & Bondi, J. (2010). Curriculum development: A guide to practice (8th ed.). Columbus, OH: Pearson.

Willis, J. (2006). Research-based strategies to ignite student learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Wolterstorff, N. (1994). Until justice and peace embrace. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Woolfolk, A. (2010). Educational psychology. Columbus, OH: Merrill.